Philippines: The place that changed everything

After an eight hour delayed flight, I arrived at a small terminal in Manila’s airport in the middle of the night. It was quiet and nearly empty aside from the dozens of Christmas tree decorations, and outside near the bus station I met my cousin whom I hadn’t seen in years.

Austin has been in the Philippines for months, living with his girlfriend and her family a few hours outside of the city in a town called Balanga. They invited me to stay with them and warned that aside from the occasional missionaries and middle aged men looking for Filipino brides, I was one of the only foreigners to have visited this city, and the first and only western woman the locals would ever see in person. I couldn’t wait.

We boarded an old bus in the terminal with ripped and dirty plastic seat covers and small cockroaches crawling up the walls. It was brightly lit and crowded and chilly, and my cousin and I spent the 3.5 hour ride catching up on life. Normally when I’m introduced to a new country and culture it’s through locals and there’s a language barrier to overcome, but having family who has been living here and integrated into their society makes for an entirely different experience.

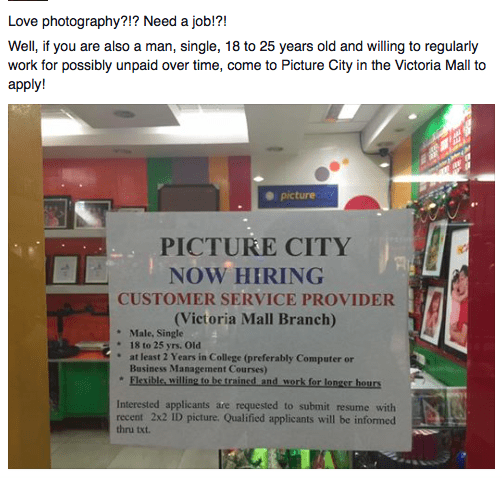

Austin explained the corruption that is so prevalent in their working class, why they are so poor and why it’s nearly impossible for them to improve their living situation. The minimum wage is not honored or regulated by the government. Companies take salary deductions—for example, if a fast food worker spills food on the ground, the customer cost of that item is deducted from their paycheck. They are forced to take home unused food that is about to expire and they will take the cost out of their paycheck regardless. Sometimes at the end of the pay period they end up actually owing money. Many companies make workers sign on as a contractor so they don’t have to provide benefits but are stuck in a 6 month contract. If the worker decides to leave, they’re put on a “blackmail” list which makes it very difficult for them to become hired in the future. To make their unemployment numbers look good, companies will hire more staff and simply cut the hours of the other workers, who can’t do anything about it since they are under contract. And employers aren’t accommodating with individual schedules so they can’t get a second job. Discrimination is allowed—many establishments will only hire between the ages of 18-25 and of a certain gender and/or stature (when physical capability has no relevance to the work). The minimum wage is not honored and the system is designed to keep them stuck and poor forever. Here’s a couple of signs Austin has seen around town and posted…

They can’t afford a visa to leave the country and even if they could they most likely wouldn’t be accepted. Parents ship their kids to the Middle East to wait tables where they will make $300-$400 a month (which is more than the average family receives working locally) and the kids send the money home to help support the family. Sex trafficking is a very real problem—sadly it’s also their solution to the problem. Single mothers with no other way to provide for their children, and parents selling their daughters to foreigners in order to support their family.

I was horrified hearing the stories Austin had learned of and witnessed during his time there. There’s no one these people can go to—the government turns a blind eye while the companies turn a profit. Austin expressed interest in approaching government officials and making a documentary to bring attention to this issue to a wider audience. I would love to get involved somehow but there wasn’t much I could do on this short trip. It’s a big problem to tackle but you have to start somewhere. Awareness is the first step.

With some background knowledge on the struggle of the working class, I entered Balanga city and was transported via tricycle (a covered motorcycle with a small side car) to their street for 50 pesos (around $1). We walked past the metal gates and in the door at around 4am, greeted warmly by Tita (Mom) while Tito (Dad) carried my bag inside. It was a typical Filipino living arrangement: a family of eight (five sons and one daughter, ages nine to thirty) living in a two bedroom house smaller than my living room back home. Tito, Tita and the two youngest sons sleep in their room while Austin and Shy (his girlfriend) stay in the second room. The rest of the sons sleep on the living room floor when they are around (one is currently working in Saudi).

A hand built plywood box serves as a couch and dining table, and until recently they only owned one small mattress—Shy was sleeping on cardboard before Austin moved in and provided one.

There is no running water during the day, no hot water at all, no shower and the toilet is a bowl on the ground. I’ve been in similar situations while staying in villages trekking in northern Thailand and Vietnam, but this is different. It’s not a guided tour or a popular backpacking excursion—this is their everyday life, their own home, their family they’ve invited me into.

Still groggy from the lack of sleep the night before, I woke up the first day to Austin handing me a stack of fabric. It was Sunday morning, their church’s 22nd Anniversary, and they had traditional Filipino attire made for me to wear for the big celebration. The smell of live crabs and shrimp soaking in the kitchen all night seeped throughout the home as Tito prepared meals for the days’ festivities. I laid out the five different garments and proceeded to dress myself in the unfamiliar costume. When I emerged, a neighbor saw my failed attempt through the window and came inside to help. She laughed as she removed the dress I was wearing as a skirt and the top I had laced up backwards, helping me arrange and secure everything properly while her sweet daughter stared up at me in wonder, never breaking her gaze.

We walked down their street to the church, my first time stepping out into the daylight with tricycles and motorbikes whizzing by while locals stopped in their tracks to witness this strange white woman draped in a festive Filipino gown. Every head turned as I entered the building and took a seat, trying not to disrupt the service. There were stares and smiles and whispers, and I politely waved and smiled back, feeling instantly at home as the band played and choir sang. The sermon was mostly in Tagalog, their native language, with English words and sentences randomly interjected. They call this “Taglish”, and I tried to follow along to the powerpoint presentation of lyrics, biblical stories and diagrams. Young women in flowing dresses appeared before us, gracefully moving to choreographed dances they’d been practicing for weeks. We all joined hands and sang and swayed to the music as tears welled up in eyes across the room. This was clearly a very important day to the members of this church who call it their second home, intensely dedicated and devoted to God. You’ll find his presence everywhere here in the Philippines—it’s not debated or even thought of as religion, just simply their way of life.

Unlike what we see back in the states, the church here loves and accepts everyone without judgment. People feel free to be whoever they want, like the sweet openly gay teen who was loved and treated just like anyone else in his peer group. After the service ended, Tita took my hand and brought me in their group to take pictures—I was part of their family now. Across the room there were nothing but smiles and laughs and people holding hands and embracing. They’re a very affectionate culture which I absolutely love and wish we had more of back home.

“Day by Day” is the name of their ministry, and its symbolism was clear right away. They live off of what little they have, finding ways to survive and support their family. As Americans, and perhaps much of the developed western world we’re constantly looking to the future. The present is never quite good enough so we dream and plan and set goals and convince ourselves that one day we’ll get what we want, life will be better and we will be happy. But these people can’t do that. They can’t save money and buy “stuff” and plan retirements and live or even go where they want. Their goal is to make it through each day with a roof over their heads, their families fed and safe. If they can go to sleep each night with only that, they feel blessed. While we’re lying in our warm comfortable bed at night complaining about our DVR being too slow, they’re boiling water to bathe themselves from a bucket after staying up all night making paper lanterns earning $0.35 per hour to survive. But all that matters is that they have their family—everyone in the community is family and they band together and help and love each other, living only in the moment, day by day.

James, the youngest son of the family I was staying with, proudly showed me off to his friends as they crowded around me. They studied my features and asked me my name and where I was from and how old I was. They guessed I was 16 and 18 and erupted in laughter, running and telling their parents, probably not much older than me, that I was 30 years old. The dancer girls were equally as curious and friendly, and we took selfies together and became Facebook friends. I borrowed clothing from Shy and joined the rest of the congregation downstairs to a home cooked feast of shrimp, crab, fish, pork, veggies, rice and fruit. We sat on plastic stools as the littlest kids played with confetti and bottles of orange soda were passed around. We ate until we were full, but even more filling was the overwhelming presence of love and community—much more than that little church can contain. It pours out into the streets from every home in Balanga and passed down through generations as if it’s written into their DNA. Especially the children. Oh, those precious beautiful souls.

James had expressed that a few kids in his school were being mean to him, so I told him I’d protect him and make sure they were nice. I walked him to school one day, not knowing what to expect. Two of his classmates came by and walked with us, holding hands along the way with James in the middle to keep him safe.

When we arrived, the stares and whispers and giggles began, and once word began to spread between the children, the entire school came out to stand witness. It was quite possibly the sweetest thing I’ve ever seen, and now I also have a slight understanding of what it’s like to be a movie star. Fortunately, Austin was able to capture the reaction of a hundred Filipino children who’d never seen a foreign girl in person:

They loved posing for photographs, and their joy and curiosity is easily captured in still images:

I had to leave before disrupting the class, but couldn’t stop smiling for a solid hour. Someone mentioned they thought I was the Virgin Mary and James certainly became the most popular kid in school that day. Word had traveled throughout the neighborhood and back at home, the kids stood at the window and watched me all day and night. It was slightly unsettling but strangely flattering at the same time.

As soon as James returned home he ran over and curled up next to me, telling me all about his day and asking if we could have a dance party. He did flips and handstands on the bed and told me he probably broke his arm. I assured him he didn’t, to which he seemed comforted by and continue to dance. He told me his biggest wish was to go swimming in a pool and be an angel so he could fly and have blond hair and blue eyes because he wished he was American. I told him he was perfect the way he was and that he’s actually happier than most of the American boys his age. He couldn’t believe this, and I explained that a lot of kids back home don’t get to be free and play like he does because they are too busy or inside of their rooms all day on their computers or video games and don’t have as many friends or big families who loved each other very much like he had. He liked that response too, and told me I was his guardian angel because I protected him from the mean kids at school and bought him a toy at the market and made sure his arm wasn’t broken. He called me “ah-tay” (big sister) and never left my side.

Christmas is a big deal here in the Philippines. I thought it was in America, but here they start celebrating September 1st, every year. Bells and garlands in the streets, music playing in stores and nativity scenes on homes and buildings—it follows you wherever you go. Four months of Christmas (and New Year’s) cheer. The family’s business is making Christmas lanterns.

They craft thousands of them every year, by hand, carved from stalks of bamboo, glue and plastic. The attention to detail is impressive and their commitment to months of working all night, outside under a porch light with family and neighbors gathering to help, for mere pennies, is inspiring to say the least. I was curious to try so one night I sat out on the porch with Tito while we chatted about Filipino celebrations and traditions and he let me carefully glue a bamboo star together.

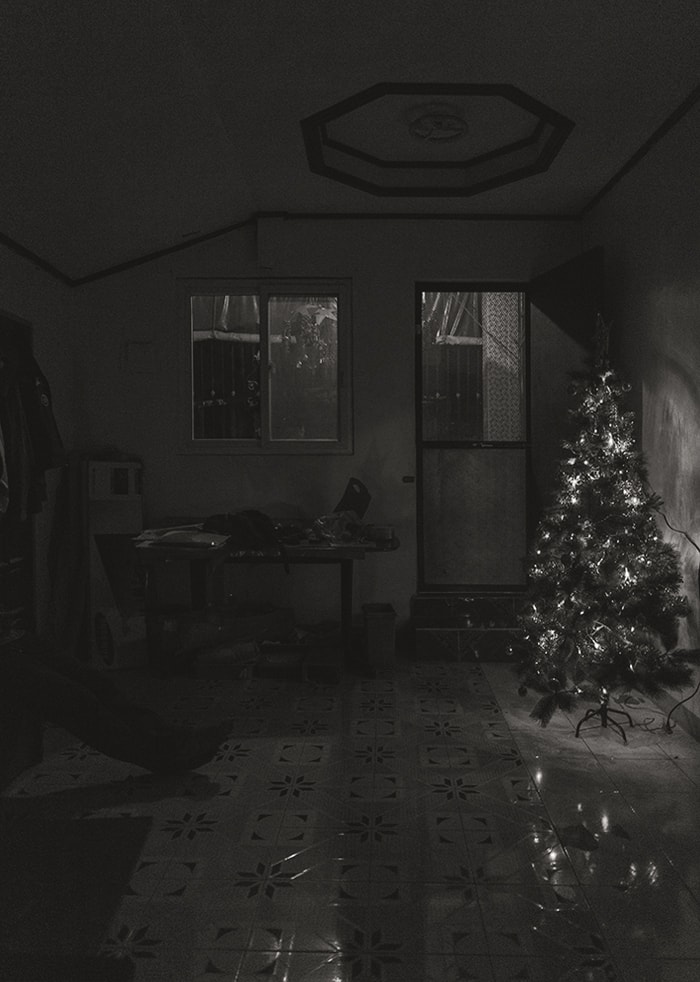

On our last night, I wanted to thank the family for their hospitality and repay them in some way, so I had them choose their favorite restaurant and treated them to one last big family feast. That didn’t feel like enough though, so I asked Austin what would be a really special gift. Something they would absolutely love but could never buy for themselves. We threw a few ideas around and then he mentioned that they’d never had a Christmas tree before. Not even Tito nor Tita had one growing up. I couldn’t imagine my holidays without one and, especially in a culture that idolizes this time of year, I made it my mission to find one.

We took a tricycle out past town and found the one store that had one tree. It was small and humble, but I knew they would love it. I bought fancy lights and garlands and ornaments, and we shoved it into the trike and told Tito and Tita to take the boys and go ahead to the restaurant before us so we could set up the tree to surprise them. I put my tree decorating skills to the test and managed to get everything set up in thirty minutes with Shy at my side. She had the biggest grin on her face, honored to help me decorate her first tree and watch it all come together, and most excited about placing the star at the top, just like she’d seen in American movies. The neighbor kids in the alleyway heard the commotion and ran to the window, staring in awe at the first Christmas tree they’d ever seen. One of the little girls began to cry and I didn’t know whether to feel good or heartbroken about it. When I turned the lights off and the tree lit up it was pure magic—the children were captivated and I couldn’t wait for the family to see. It was perfect.

We joined the family for dinner and I sat next to James who had saved a seat just for me. We passed around shrimp and rice and veggies and chop suey and pork and orange soda. Before I left, my family and I always had weekly dinners at home and this felt just like that—home. We had meaningful conversations and it was all laughs and smiles, until James burst into tears and ran to his mother, sobbing. I didn’t understand what was wrong until she told me that he was crying because he didn’t want me to leave. I tried to comfort him but to no avail—he cried in her arms for the rest of dinner. I told him I had a surprise waiting for him that would make him really happy. He was inconsolable though, and I held his hand as we walked back home, tears landing in the dirt as he stepped. We approached their house and Austin ran up first to unlock the door. I opened it and watched as Tito and Tita stood in the doorway, shocked and trying to comprehend what they were witnessing. They slowly walked forward, speechless, as the other boys seemed equally as stunned. After the realization set in, tears welled up in Tita’s eyes and they stood around the tree, examining the ornaments and touching the branches.

I asked if they liked it but it was clear that this meant so much more than that. James was still upset about my departure and couldn’t muster a smile, but he still promptly ran to the computer and turned on Christmas songs. I’d bought him a Santa hat and placed it on his head as they gathered in front of the tree for their first Christmas family photo.

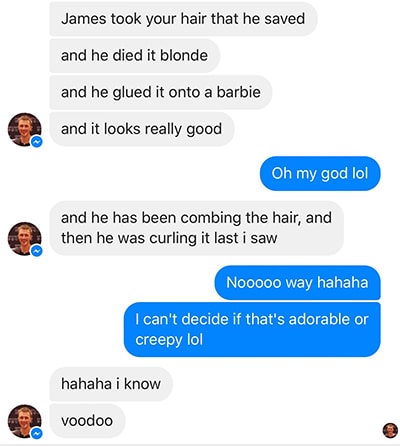

Later that night I was helping one of the brothers with his homework and saw James peeking out through the bedroom window, seemingly in happier spirits. I called him over and we played catch and soccer in the living room and he asked if he could sleep next to me that night. I let him brush my hair and he collected the strands from the brush, admired their light brown color, placed them into a sock and said he’d keep it forever as a memory of me. I climbed into bed and he reached around me, grasping with his little arms and sniffling as he tried to fall asleep. It was hard not to tear up as well, realizing that this part of my trip had changed me forever. This meant more than all the crazy adventurous nights—this is the family I dreamed I’d have of my own someday.

I did what I could to show my gratitude and make their days a little brighter while I was here, but they’ve given me an even greater gift. One of deeper understanding, gratefulness and humility. Only in the Philippines are the people as pure and beautiful as the pristine land and oceans.

Filipinos are said to be the happiest people on earth, and I’m so thankful for the opportunity to witness it firsthand and find out why. People wonder how they are so happy with so little, but it makes perfect sense. Having less physically allows for more room to let what really matters in. What you own ends up owning you, and a life filled with “stuff” will only clutter your mind. If living with nothing more than you need is one key to happiness, letting your guard down and expressing your emotions in the purest form is another.

Over dinner one night, Austin shared what he’d observed from the culture and what struck him most is their ability to keep their feelings simple and uncomplicated. He explained that if they are upset or sad or happy, they will express it without holding back in fear of judgment. They will cry and laugh and let their guard down. They don’t overanalyze or hold grudges or seek revenge. In the same way that they live with less physically, there is also no emotional baggage and drama controlling their thoughts which so many of us seem to feed into and thrive off of back home. I’ve witnessed firsthand how downsizing and simplifying your life can facilitate true happiness, but perhaps more important is stripping away all the complexities of our thoughts and just reacting from raw emotion, not letting our past experiences or egos get in the way. Easier said than done, but we can all learn something from the way they live. They’ve never had a chance to read my favorite book—the one that made it all click for me during my first flight to Bangkok—but they’re already living it. They just get it. Living in the moment, love in the highest form—they are enlightened. And that, I believe, is why they are collectively the happiest people you’ll find.

I’ve kept in close contact with Austin and the family since leaving, and some things are just too good not to share. Like this message the night after I left:

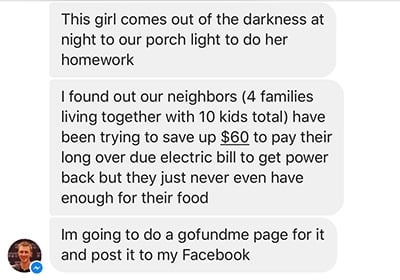

On a more somber note, he also sent me this photo and message just the other day.

He didn’t ask me to share, but I want to. I want others to see what these families face on a regular basis. Things to keep in mind when you’re celebrating Thanksgiving this year. I know I will be.

Austin could easily just pay the $60 himself, but he’d rather make others more aware and give them an opportunity to help. If you feel inclined to do so, you can read and learn more on his gofundme page here.

As I finish this post I started weeks ago, 33,000 miles above the Pacific Ocean en route home to San Francisco, I can safely say that the Philippines are my favorite country, and the perfect way to end this journey. I have another post lined up full of photographs of the most amazing islands, beaches and lagoons in the world. The last two weeks of my trip were spent in a state of bliss, enjoying every minute of my surroundings and simply existing—hence the lack of posts during my time there (though don’t forget I’m always checking in on instagram). I still have a lot to process and share, but for now, I’ll end things here. Goodnight and see you again soon, Asia.